Today’s blog is dedicated to an amazing woman, Dee (pronounced Day) de Smalen, my mother-in-law. Today she turns 90! Happy Birthday Dee, Hartelijk Gefeliciteerd met je verjaardag!!

She grew up in the former Dutch East Indies, on Java. Her parents, pictured below, worked for the Dutch government and ran two orphanages for a mixture of Dutch and Indonesian children. These schools were set up as part of the Ethical Policy in the region which was introduced by the Dutch to improve living conditions for the indigenous population. In March 1942 their lives changed irrevocably when the Japanese invaded West Java.

Family photo taken on Java during the occupation. Dee Kiesling on the right in a bibbed gingham dress.

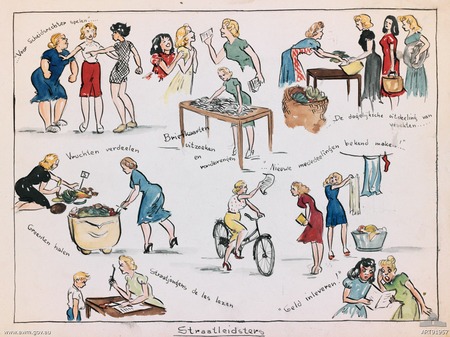

Published in Herstoria, this article is an account of the bravery and resilience of Dee, her sister and mother during their internment in Japanese POW Camps.

I was sixteen when we had to go into the camp. We spent the first night in a monastery. We were all in shock. My mother was reeling from the trauma of being separated from father. We stayed there a few days and then we were moved to Bandoeng, the capital of West Java province. Camp Karees was a collection of houses in the European section of Bandoeng, fenced off with gedek (plaited bamboo sheets) and topped with barbed wire. The Japanese guarded the circumference. The camp held 6000 internees. We moved into houses that had been recently vacated by the Dutch. My mother, sister Ems and I had to share a house with seven other families. Within that house each family was assigned a room.

There was a camp kitchen which served one warm meal a day at first and later on, after the poorly constructed ovens collapsed, we were given raw ingredients which we had to prepare ourselves. My sister and I cooked over a charcoal fire and became very adept at making meals from our rations. Our speciality was ‘Crème de Trasi.’ Trasi is shrimp paste which we used to fry and mix with rice.

To get extra protein we hunted frogs after sundown.

The three of us sneaked out together, using a pillowcase to put our catch in. We usually caught about seven or eight and back at camp mother chopped off their heads and skinned them. Their little torsos with their broad shoulders and thin hips looked just like a man’s body. When you salted them their nerves twitched and made their legs dance. We boiled them in water and they tasted like chicken. After a while the Japanese forbade it as the frogs kept the insect population down and mosquito numbers were turning into plague proportions.

My mother helped in the hospital, nursing the sick. Asides from the lean rations conditions were fairly good at this stage. We made friends with a woman from the Jordaan (Amsterdam old neighbourhood), equivalent to a London Cockney. A young newlywed she had a beauty salon and because she lived in Bandoeng before the neighbourhood was ghettoised she still had a lot of potions and creams. She was loads of fun, always ready with a smile and a joke. She helped keep our spirits up. We traded cooked meals with her in exchange for beauty treatments.

Ando-san, a Japanese guard was about eighteen years old. He confided in my mother that he hated the war and the way the women were being treated. They communicated in Malay. Every so often he would smuggle us treats, a tin of sardines or an egg passed through the bamboo fence. Mother won Ando’s trust enough to ask if he could find out where my father was interred. A few days later Ando came and told us that father was in Tjimahi, a men’s camp in Bandoeng. Mum wrote him a letter and because of her work in the hospital she was able to get him a pair of specs from a patient that had died. We were all over the moon when Ando brought a letter back from father. He wrote that he was well and thanked mum for the specs. He weighed 65 kilos by then, hungry all the time, but still in good health.

Once I remember, Ando asked us to meet him at the sentry box after dark. Ems and I were totally without guile and went to meet him without considering possible dangers involved. Our trust in him was rewarded. He had brought us a Chinese takeaway! It was the first decent food we had eaten since entering the camp. The last time we saw him he was in tears, devastated by the news that he had to go and join the fighting. We never knew what became of him.

some women exchanged ‘favours’ with the Japanese in the hope of getting better treatment.

My sister and I, although in our late teens, were naïve and had no idea that some women exchanged ‘favours’ with the Japanese in the hope of getting better treatment. The Japanese whores they would later be labelled. After the war we heard of the appalling treatment of the inaccurately named ‘comfort women.’ The Japanese handpicked single women aged 17 – 28 and took them from the camps to work as prostitutes for their officer elite. They were raped systematically every day. Many of these women were virgins. There were accounts of older, married women asking to be taken instead of the younger women who were innocent of sex. They thought they would be able to handle enforced prostitution better.

We spent eighteen months in Bandoeng and then had to make a 36 hour trip by train to Amberawa in central Java. The train’s windows were blocked off and we were all huddled together like cattle. There were no toilets. My sister had diarrhoea and she had to go out onto the carriage balcony to do her business and then wipe it off with a broom.

We had to walk from the train to Banjoe Biroe, our next camp, with our few possessions and a rolled-up mattress on our backs. We had no separate rooms anymore. This camp was a prison before the war. We slept in a barrack on a raised platform which ran the length of the building. My mother took us into the corner which she anticipated would offer some cover from the Japanese when they checked in on us. We had 45 centimetres per person. Here we had to forgo any ideas of privacy. We washed in full view of the guards. After a while we became immune to their gaze. Toilets were a long plank with holes where you defecated into an open sewer. Dysentery soon became rife.

Camp Karees was cushy in comparison with Banjoe Biroe. Young healthy women such as myself were put to work. In pairs, we had to carry big metal drums containing hot food from the kitchen to the barracks. It was a precarious task. One either side of the barrel, we lifted it off an un-mortared brick furnace with a bamboo stick placed through two handles at the top.

We had to work outside the camp as well. Chopping trees down for firewood. As we worked Indonesian kids would watch us from behind another outer fence. Every so often we had a chance to trade with them. We would give them a piece of textile we had managed to salvage from our former lives in exchange for an egg. We smuggled it back into camp inside the leg of our baggy knickers. Every time we entered the camp we had to bow three times in deference to the Japanese sentry. We were never discovered. Some women were caught and got punished for similar misdemeanours.

Women would be punished at roll call or Tenko. They had their hands tied behind their backs and their arms suspended from a purpose-built beam.

Women would be punished at roll call or Tenko. They had their hands tied behind their backs and their arms suspended from a purpose-built beam, lifted up high enough so that their toes just touched the ground. The Japanese guards would scream at them, administering the occasional whiplash. They were left like that for hours in the blistering sun.

Sometimes in the evening, to stave off hunger pangs, we would get together in our barrack and fantasise about food. Writing down our favourite recipes on little scraps of paper and exchanging them. Sleep was a good way of avoiding hunger but that was difficult because of the bedbugs. The Japanese gave us a thick tarry substance which was supposed to repel them. My mother saved that though and with a few bits of rice my sister and I managed to smuggle from the kitchen we cooked a few extra handfuls in a tin using the tar as cooking fuel.

In the last six months in the camp we worked in the kitchens. This was a privileged position and perhaps looking back on it meant the difference between life and death. We had thin tapioca for breakfast. Rice and watery sayor (green vegetable mix) for lunch and sometimes a piece of swede in the evening. People were dying every day from malnourishment and dysentery. Our periods stopped which had its upside as we no longer had to bother washing out the cotton towels that we used to absorb the flow.

We caught snails outside the camp and it was our job in the kitchen to prepare them. When they boiled they turned into a grey viscous substance and when we added some vegetable stock the mixture turned a foul shade of green. We gave this to the women in the sick bay in the hope it would build them up. On average there were three or four deaths per day. On a bad day that could go up to seven.

August 1945 the Japanese capitulated. When our Japanese sentries disappeared our first thoughts were of escape. But where could we go?

We had no news of the outside world and the way the war was progressing so it was a shock to us when we heard that in August 1945 the Japanese had capitulated. When our Japanese sentries disappeared our first thoughts were of escape. But where could we go? Our former home was miles away and leaving the camp was dangerous because of the hatred of the local people towards the Dutch.

The Indonesians started attacking the camps. The British allies and the Ghurkas had arrived by then and were appointed to guard us from the Indonesians. Before that time though, there was a chaotic period when many civilians were massacred by the native people.

Eventually lists of missing people were distributed around the camps by the Red Cross. We searched for father’s name.

He was not on any list but we received a postcard from the hospital in Batavia (modern Jakarta) informing us that daddy was very sick. A Sister had written that he desperately wanted to see us. Camp security warned us against leaving the camp. But my mother was a very determined woman.

We got a lift from the camp to the station on the back on an ox wagon. It was chaos on the station platform with hoards of people squashing onto the train. My sister and I and managed to squeeze through the crowd to get on the train but mum was crowded out and left on the platform. We had to haul her in by her arms though the window. God knows what would have happened if we had got separated then. It took three days to get to Batavia. The train stopped at night. The rails were broken and had to be repaired in places. By the time we reached the hospital in Batavia we were told that daddy had died a week before of starvation. The professional care that the allied doctors gave him, came too late. We had missed the last chance to see him alive.

We did not know what to do then. Going back to camp was not an option and we needed to be safe. Mum asked around in the hospital and she found some old friends that we could stay with in Batavia. We stayed there for a month and put our names on a list to get a ship back to Holland.

After a few weeks of waiting and hoping, a handsome young man walked up the garden path. Dressed in a white sailor’s uniform. Everything about him was fair, his skin, hair and clothes. I had my hairpins in and looked a total sight. He had sailed over as First Mate on a Dutch ship bringing allied forces to Indonesia. The people we were staying with were relations of his. He was looking for surviving family members.

Mum said ‘Rob de Smalen, you’re the spit of your dad!’ She was a friend of his father’s. I had forgotten by then, but Rob and I had known each other as kids and had played together. He had three days leave before his ship returned to the Fatherland. Fate took over from there. We heard that we could sail back to Holland on his ship! During the journey back to Holland we fell in love. In 1949 after a long engagement, we got married and a year later I gave birth to my first son.

What an extraordinary story of courage and survival. I don’t know how to say it in Dutch but I wish your mother-in-law many more happy birthdays!

LikeLike

Thanks, Jill. I already passed your best wishes on. Happy Birthday in Dutch is a real tongue twister. Hartelijk gefeliciteerd met je verjaardag..Luckily one gets plenty of practise as it’s traditional to congratulate everyone in the family, friends and the neighbours!

LikeLike

What an interesting and impressive story! Many good wishes to your mother-in-law for her birthday. My ex husband was an infant in the camps. Interestingly the same camps – Bandung and Ambarawa. Later, we ourselves lived in Salatiga close by for 3 years. Not sure about Banja Biru. Bernard’s family never talked about the camps much, in fact they more or less denied any hardship at all. I always felt that his early experiences also played a part in our problems together. Very sad actually.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and commenting, Sally. It’s sad that those experiences can have such a far reaching effect on people’s lives. It was certainly fascinating to hear about the details of everyday life in the camp from Dee. So much of those day to day events get overlooked in the greater sweep of history.

LikeLike

Hartelijk Gefeliciteerd met je verjaardag to your mother-in-law! What a story. It’s amazing what people have lived through. Also amazing the way people find each other during and after such horrendous events, the way Rob came back into Dee’s life.

LikeLike

Thanks, Chris. I will pass your birthday wishes on! Fact is truly stranger than fiction sometimes. Given they didn’t have all the technology back then that makes it easier to find people, it is amazing that lives can come together so unexpectedly.

LikeLike

So true. Today it’s pretty common to see long lost friends reunited, but back in those days, it was practically a miracle.

LikeLike

Wow, this is our Aunt and Uncle. We hadn’t seen them in many years. Tante Dee looks wonderful but sadly Uncle Rob is no longer with us. This story has overtones of our father’s experiences in similar prison of war camp in Indonesia. Dad’s first memory of the war was his mother dying of cellulitis (a serious skin condition) in her legs two weeks before the war started. Next memory was standing in an office in front of Japanese soldiers, with his father and sister, experiencing loaded guns pointed in their backs. When I asked Dad why his family were in Indonesia, Dad replied that his father was the secretary of the Dutch government in Indonesia, and had witnessed the signing of documents to make Indonesia independent of the Netherlands. Dad’s memories of the camp were not good and so was very reticent to share many stories. Dad remembered his father experienced many horrific times being beaten at the hands of the Japs. His father had been a tall overweight man at the start, but by the end of the war, had shrunk considerably in size and stature. We were fortunate to hear the positive stories of Dad’s time and one of those was also being fed smuggled food in from outside the compound. Dad ended up being brother-in-law to Uncle Rob and brought his younger sister, Bep, as his bride to Western Australia in 1955. Dad (Dolf de Smalen) passed away 18th April, 2009 and Bep is still living in Kensington Park Nursing Home.

LikeLike

Thanks, Linda for commenting and sharing your Dad’s experiences. I shall pass this on to Dee, my mum-in-law. I am sure she will be thrilled to read it!

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing your mother in-law’s story. My mother (born in 1941), late aunt, and grandparents were there as well (Bandoeng, Ambarawa, and my grandfather at Tjimahi). We’ve heard bits and pieces of the story our entire lives, but have insufficient written history. And most of what we’ve heard is from my mother who reconstructed it by asking her mother. My grandparents couldn’t really talk about it and it’s sad that so much of their story has died with them.

I recently discovered a written account by AA Fermin, which is a very close replica of my mother’s story:

Click to access MIJN-VERHAAL-2017-tekst-Ad-Fermin.pdf

LikeLike

Thank you, Victoria for sharing your family’s history. I was so glad to get this article published in Herstoria, and also on my blog. I’m not sure if it was cathartic for my MIL but she enjoyed reading it and was flattered that I showed interest in her. Before the interview I had only heard anecdotes of her experiences so it was satisfying to put it into a cohesive account. I look forward to reading the file by AA Fermin.

LikeLike